|

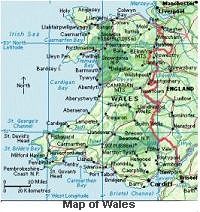

WILD WALES

Contents

Travellers in Wales

The Journey

Llangollen and Encounters

with the Welsh Language

Travelling South

Swansea

Conclusion

Travellers in Wales

This treatise is follow-on from the previous article on Giraldus Cambrensis, which

dealt with the journey made around Wales in the company of Archbishop Baldwyn of

Canterbury in the year 1188.

George Borrow made a similar journey around Wales in 1854, mostly on foot. George Borrow made a similar journey around Wales in 1854, mostly on foot.

The traveller and writer, George Borrow (1803 - 1881) was born in Dumpling Green,

a small hamlet on the outskirts of East Dereham, 15 miles west of Norwich of a Cornish

father and Norfolk mother. He was educated in Edinburgh High School and in Norwich

at the King Edward VI Grammar School in the Cathedral Close.

In Norwich, on the hills of Mousehold, above the Cathedral, he spent time in the

company of the gypsies. It was probably from listening to their tales of wandering

that his urge to travel came.

Education over, he was articled to a solicitor. During his apprenticeship, he edited

Celebrated Trials, and Remarkable Cases of Criminal Jurisprudence (1825),

and then he packed his bags and travelled not only all over the British Isles, but

also as an agent for the Bible Society across Europe.

Finally he married a well-to-do widow and settled near Oulton Broad in Suffolk. He

published a number of books based partly on his own experiences and travels. In 1841

came 'The Gipsies of Spain' followed in 1843 by the 'Bible in Spain', 'Lavengro'

in 1851 and 'Romany Rye' in 1857. As a result of his travels Borrow wrote "Wild

Wales", in 1862. An enthusiastic traveler and eccentric, Borrow had an extraordinary

talent for languages. Welsh was one of many languages he learned in Norwich as a

young man, taking lessons from a Welsh groom. He must have been an ideal learner

to have mastered the intricacies of Welsh grammar.

Many years later, in the summer of 1854, he came with his family to Wales - to enjoy

its people, language and scenery, in that order. That he enjoyed himself immensely

will be apparent to any reader: 'wherever I have been in Wales I have experienced

nothing but kindness and hospitality'.

Wild Wales is neither a factual nor a sober account of picturesque scenery: it is

too dramatic and cheerful a book to be categorised so easily. Borrow looked for the

wildness of Wales not only in the scenery but also in the people, and he found it

in 'the real Welsh' and in tinkers, gypsies and other down and outs.

His encounters with these people read like scenes from a novel or a piece of theatre.

In his introduction to 'Wild Wales' Borrow described Wales as an interesting country

in many respects, and deserving of more attention than it had hitherto met with.

Though not very extensive, it is one of the most picturesque countries in the world,

a country in which Nature displays herself in her wildest, boldest, and occasionally

loveliest forms. The inhabitants, who speak an ancient and peculiar language, do

not call this region Wales, nor themselves Welsh. They call themselves Camry, and

their country Cymru, or the land of the Cymry. Wales or Wallia, however, is the true,

proper, and without doubt original name, as it relates not to any particular race,

which at present inhabits it, or may have sojourned in it at any long bygone period,

but to the country itself. Wales signifies a land of mountains, of vales, of dingles,

chasms, and springs. It is connected with the Cumbric bal, a protuberance, a springing

forth; with the Celtic beul or beal, a mouth; with the old English welle, a fountain;

with the original name of Italy, still called by the Germans Welschland; with Balkan

and Vulcan, both of which signify a casting out, an eruption; with Welint or Wayland,

the name of the Anglo-Saxon god of the forge; with the Chaldee val, a forest, and

the German wald; with the English bluff, and the Sanscrit palava - startling assertions,

no doubt, at least to some; which are, however, quite true, and which at some future

time will be universally acknowledged so to be.

The Journey

In the summer of the year 1854 myself, wife, and daughter determined

upon going into Wales, to pass a few months there. We are country people of a corner

of East Anglia, and, at the time of which I am speaking, had been residing so long

on our own little estate, that we had become tired of the objects around us, and

conceived that we should be all the better for changing the scene for a short period.

We were undetermined for some time with respect to where we should go. I proposed

Wales from the first, but my wife and daughter, who have always had rather a hankering

after what is fashionable, said they thought it would be more advisable to go to

Harrowgate, or Leamington. In the summer of the year 1854 myself, wife, and daughter determined

upon going into Wales, to pass a few months there. We are country people of a corner

of East Anglia, and, at the time of which I am speaking, had been residing so long

on our own little estate, that we had become tired of the objects around us, and

conceived that we should be all the better for changing the scene for a short period.

We were undetermined for some time with respect to where we should go. I proposed

Wales from the first, but my wife and daughter, who have always had rather a hankering

after what is fashionable, said they thought it would be more advisable to go to

Harrowgate, or Leamington.

On my observing that those were terrible places for expense, they replied that, though

the price of corn had of late been shamefully low, we had a spare hundred pounds

or two in our pockets, and could afford to pay for a little insight into fashionable

life. I told them that there was nothing I so much hated as fashionable life, but

that, as I was anything but a selfish person, I would endeavour to stifle my abhorrence

of it for a time, and attend them either to Leamington or Harrowgate.

So our little family, consisting of myself, my wife Mary, and my daughter Henrietta,

for daughter I shall persist in calling her, started for Wales in the afternoon of

the 27th July, 1854. We flew through part of Norfolk and Cambridgeshire in a train

which we left at Ely, and getting into another, which did not fly quite so fast as

the one we had quitted, reached the Peterborough station at about six o'clock of

a delightful evening. We proceeded no farther on our journey that day, in order that

we might have an opportunity of seeing the cathedral: and so towards Wales they travelled.

On arriving at Chester, at which place we intended to spend two or three days, we

put up at an old-fashioned inn in Northgate Street, to which we had been recommended;

my wife and daughter ordered tea and its accompaniments, and I ordered ale, and that

which always should accompany it, cheese. "The ale I shall find bad," said

I; Chester ale had a villainous character in the time of old Sion Tudor, who made

a first-rate englyn upon it, and it has scarcely improved since; "but I shall

have a treat in the cheese, Cheshire cheese has always been reckoned excellent, and

now that I am in the capital of the cheese country, of course I shall have some of

the very prime." Well, the tea, loaf and butter made their appearance, and with

them my cheese and ale. To my horror the cheese had much the appearance of soap of

the commonest kind, which indeed I found it much resembled in taste, on putting a

small portion into my mouth. "Ah," said I, after I had opened the window

and ejected the half-masticated morsel into the street, "those who wish to regale

on good Cheshire cheese must not come to Chester,

Having walked round the city for the second time, I returned to the inn. In the evening

I went out again, passed over the bridge, and then turned to the right in the direction

of the hills. Near the river, on my right, on a kind of green, I observed two or

three tents resembling those of gypsies. Some ragged children were playing near them,

who, however, had nothing of the appearance of the children of the Egyptian race,

their locks being not dark, but either of a flaxen or red hue, and their features

not delicate and regular, but coarse and uncouth, and their complexions not olive,

but rather inclining to be fair. I did not go up to them, but continued my course

till I arrived near a large factory. I then turned and retraced my steps into the

town. It was Saturday night, and the streets were crowded with people, many of whom

must have been Welsh, as I heard the Cambrian language spoken on every side.

Llangollen and Encounters with the Welsh Language

On the afternoon of Monday I sent my family off by the train to Llangollen,

which place we had determined to make our head-quarters during our stay in Wales.

I intended to follow them next day, not in train, but on foot, as by walking I should

be better able to see the country, between Chester and Llangollen, than by making

the journey by the flying vehicle. As I returned to the inn from the train I took

refuge from a shower in one of the rows or covered streets, to which, as I have already

said, one ascends by flights of steps; stopping at a book-stall I took up a book

which chanced to be a Welsh one. On the afternoon of Monday I sent my family off by the train to Llangollen,

which place we had determined to make our head-quarters during our stay in Wales.

I intended to follow them next day, not in train, but on foot, as by walking I should

be better able to see the country, between Chester and Llangollen, than by making

the journey by the flying vehicle. As I returned to the inn from the train I took

refuge from a shower in one of the rows or covered streets, to which, as I have already

said, one ascends by flights of steps; stopping at a book-stall I took up a book

which chanced to be a Welsh one.

The proprietor, a short red-faced man, observing me reading the book, asked me if

I could understand it. I told him that I could.

"If so," said he, "let me hear you translate the two lines on the

title-page."

"Are you a Welshman?" said I.

"I am!" he replied.

"Good!" said I, and I translated into English the two lines, which were

a couplet by Edmund Price, an old archdeacon of Merion, celebrated in his day for

wit and poetry.

The man then asked me from what part of Wales I came, and when I told him that I

was an Englishman was evidently offended, either because he did not believe me, or,

as I more incline to think, did not approve of an Englishman's understanding Welsh.

The book was the life of the Rev. Richards, and was published at Caerlleon, or the

city of the legion, the appropriate ancient British name for the place now called

Chester, a legion having been kept stationed there during the occupation of Britain

by the Romans.

Llangollen is a small town or large village of white houses with slate roofs, it

contains about two thousand inhabitants, and is situated principally on the southern

side of the Dee. At its western end it has an ancient bridge and a modest unpretending

church nearly in its centre, in the chancel of which rest the mortal remains of an

old bard called Gryffydd Hiraethog. From some of the houses on the southern side

there is a noble view - Dinas Bran and its mighty hill forming the principal objects.

The view from the northern part of the town, which is indeed little more than a suburb,

is not quite so grand, but is nevertheless highly interesting. The eastern entrance

of the vale of Llangollen is much wider than the western, which is overhung by bulky

hills. There are many pleasant villas on both sides of the river, some of which stand

a considerable way up the hill; of the villas the most noted is Plas Newydd at the

foot of the Berwyn, built by two Irish ladies of high rank, who resided in it for

nearly half a century, and were celebrated throughout Europe by the name of the Ladies

of Llangollen

Next morning I set out to ascend Dinas Bran, a number of children, almost entirely

girls, followed me. I asked them why they came after me. "In the hope that you

will give us something," said one in very good English. I told them that I should

give them nothing, but they still followed me. A little way up the hill I saw some

men cutting hay. I made an observation to one of them respecting the fineness of

the weather; he answered civilly, and rested on his scythe, whilst the others pursued

their work. I asked him whether he was a farming man; he told me that he was not;

that he generally worked at the flannel manufactory, but that for some days past

he had not been employed there, work being slack, and had on that account joined

the mowers in order to earn a few shillings. I asked him how it was he knew how to

handle a scythe, not being bred up a farming man; he smiled, and said that, somehow

or other, he had learnt to do so.

"You speak very good English," said I, "have you much Welsh?"

"Plenty," said he; "I am a real Welshman."

"Can you read Welsh?" said I.

"Oh, yes!" he replied.

"What books have you read?" said I.

"I have read the Bible, sir, and one or two other books."

"Did you ever read the Bardd Cwsg?" said I.

He looked at me with some surprise. "No," said he, after a moment or two,

"I have never read it. I have seen it, but it was far too deep Welsh for me."

"I have read it," said I.

"Are you a Welshman?" said he.

"No," said I; "I am an Englishman."

"And how is it," said he, "that you can read Welsh without being a

Welshman?"

"I learned to do so," said I, "even as you learned to mow, without

being bred up to farming work."

"Ah! "said he, "but it is easier to learn to mow than to read the

Bardd Cwsg."

( the reference is to 'Gwledigaeth Y Bardd Cwsg ñ The Vision of the Sleeping Bard;

a deep and philosophical book by Ellis Wynne, published in 1703 )

"I don't think that," said I; "I have taken up a scythe a hundred

times but I cannot mow."

"Will your honour take mine now, and try again?" said he.

"No," said I, "for if I take your scythe in hand I must give you a

shilling, you know, by mowers' law."

He gave a broad grin, and I proceeded up the hill. When he rejoined his companions

he said something to them in Welsh, at which they all laughed. I reached the top

of the hill, the children still attending me.

The view over the vale is very beautiful; but on no side, except in the direction

of the west, is it very extensive; Dinas Bran being on all other sides overtopped

by other hills: in that direction, indeed, the view is extensive enough, reaching

on a fine day even to the Wyddfa or peak of Snowdon, a distance of sixty miles, at

least as some say, who perhaps ought to add to very good eyes, which mine are not.

The day that I made my first ascent of Dinas Bran....

George Borrow must have been fortunate to find someone who could understand what

must have been his obvious English accent, even though he claimed to understand the

varying dialects he would have had to cope with in his conversations with the local

people.

Travelling South

The travelogue continues as George Borrow and his family make their way from North

Wales to the south where by the mid-nineteenth century the Industrial Revolution

was in full swing. Nowhere would he find more pollution and desecration of the land

than in the Lower Swansea Valley.

Swansea

Swansea is called by the Welsh Abertawe, which signifies the mouth of

the Tawy. Aber, as I have more than once had occasion to observe, signifies

the place where a river enters into the sea or joins another. It is a Gaelic as well

as a Cymric word, being found in the Gaelic names Aberdeen and Lochaber, and there

is good reason for supposing that the word harbour is derived from it. Swansea or

Swansey is a compound word of Scandinavian origin, which may mean either a river

abounding with swans, or the river of Swanr, the name of some northern adventurer

who settled down at its mouth. The final ea or ey is the Norwegian aa, which signifies

a running water; it is of frequent occurrence in the names of rivers in Norway, and

is often found, similarly modified, in those of other countries where the adventurous

Norwegians formed settlements.

Swansea first became a place of some importance shortly after the beginning of the

twelfth century. In the year 1108, the greater part of Flanders having been submerged

by the sea an immense number of Flemings came over to England, and entreated of Henry

the First the king then occupying the throne, that he would all allot to them lands

in which they might settle, The king sent them to various parts of Wales, which had

been conquered by his barons or those of his predecessors: a considerable number

occupied Swansea and the neighbourhood; but far the greater part went to Dyfed, generally

but improperly called Pembroke, the south-eastern part of which, by far the most

fertile, they entirely took possession of, leaving to the Welsh the rest, which is

very mountainous and barren. I have already said that the people of Swansea stand

out in broad distinctness from the Cymry, differing from them in stature, language,

dress, and manners, and wished to observe that the same thing may be said of the

inhabitants of every part of Wales, which the Flemings colonised in any considerable

numbers.

I reached Llan(samlet?); a small village half-way between Swansea and

Neath, and without stopping continued my course, walking very fast. I had surmounted

a hill, and had nearly descended that side of it which looked towards the east, having

on my left, that is to the north, a wooded height, when an extraordinary scene presented

itself to my eyes. Somewhat to the south rose immense stacks of chimneys surrounded

by grimy diabolical-looking buildings, in the neighbourhood of which were huge heaps

of cinders and black rubbish. From the chimneys, notwithstanding it was Sunday, smoke

was proceeding in volumes, choking the atmosphere all around. From this pandemonium,

at the distance of about a quarter of a mile to the south-west, upon a green meadow,

stood, looking darkly grey, a ruin of vast size with window holes, towers, spires,

and arches. Between it and the accursed pandemonium, lay a horrid filthy place, part

of which was swamp and part pool: the pool black as soot, and the swamp of a disgusting

leaden colour. Across this place of filth stretched a tramway leading seemingly from

the abominable mansions to the ruin. So strange a scene I had never beheld in nature.

Had it been on canvas, with the addition of a number of Diabolical figures, proceeding

along the tramway, it might have stood for Sabbath in Hell - devils proceeding to

afternoon worship, and would have formed a picture worthy of the powerful but insane

painter, Hieronymus Bosch. I reached Llan(samlet?); a small village half-way between Swansea and

Neath, and without stopping continued my course, walking very fast. I had surmounted

a hill, and had nearly descended that side of it which looked towards the east, having

on my left, that is to the north, a wooded height, when an extraordinary scene presented

itself to my eyes. Somewhat to the south rose immense stacks of chimneys surrounded

by grimy diabolical-looking buildings, in the neighbourhood of which were huge heaps

of cinders and black rubbish. From the chimneys, notwithstanding it was Sunday, smoke

was proceeding in volumes, choking the atmosphere all around. From this pandemonium,

at the distance of about a quarter of a mile to the south-west, upon a green meadow,

stood, looking darkly grey, a ruin of vast size with window holes, towers, spires,

and arches. Between it and the accursed pandemonium, lay a horrid filthy place, part

of which was swamp and part pool: the pool black as soot, and the swamp of a disgusting

leaden colour. Across this place of filth stretched a tramway leading seemingly from

the abominable mansions to the ruin. So strange a scene I had never beheld in nature.

Had it been on canvas, with the addition of a number of Diabolical figures, proceeding

along the tramway, it might have stood for Sabbath in Hell - devils proceeding to

afternoon worship, and would have formed a picture worthy of the powerful but insane

painter, Hieronymus Bosch.

He journeyed on up the valley:

I found the accommodation very good at the "Mackworth Arms"; I passed the

Saturday evening very agreeably, and slept well throughout the night. The next morning

to my great joy I found my boots, capitally repaired, awaiting me before my chamber

door. Oh the mighty effect of a little money! After breakfast I put them on, and

as it was Sunday went out in order to go to church. The streets were thronged with

people; a new mayor had just been elected, and his worship, attended by a number

of halberd and javelin men, was going to church too. I followed the procession, which

moved with great dignity and of course very slowly. The church had a high square

tower, and looked a very fine edifice on the outside, and no less so within, for

the nave was lofty with noble pillars on each side. I stood during the whole of the

service, as did many others, for the congregation was so great that it was impossible

to accommodate all with seats. The ritual was performed in a very satisfactory manner,

and was followed by an excellent sermon. I am ashamed to say that have forgot the

text, but I remember a good deal of the discourse. The preacher said amongst other

thing that the Gospel was not preached in vain, and that he very much doubted whether

a sermon was ever delivered which did not do some good. On the conclusion of the

service I strolled about in order to see the town and what pertained to it. The town

is of considerable size, with some remarkable edifices, spacious and convenient quays,

and a commodious harbour into which the river Tawe flowing from the north empties

itself. The town and harbour are overhung on the side of the east by a lofty green

mountain with a Welsh name, no doubt exceedingly appropriate, but which I regret

to say has escaped my memory.

After having seen all that I wished, I returned to my inn and discharged all my obligations.

I then departed, framing my course eastward towards England, having traversed Wales

nearly from north to south.

Conclusion

George Borrow ventured to Wales for the first time in July 1854 when, at the

age of fifty-one, he began the walk, which was to be the subject of Wild Wales. Writing

of his journey, his wife noted: "He keeps a daily journal of all that goes on,

so that he can make a most amusing book in a month whenever he wishes to do so".

He began organising his material immediately on returning home but the first draft

was not completed until 1857, the year of the publication of his Romany Rye. A further

five years passed before the publication of Wild Wales, the delay occasioned perhaps

by the chilly reception given to Romany Rye. The 1854 visit, beginning at Llangollen

on 27 July, included fairly intensive travels in parts of the north and was then

followed by a sweep down through Cardiganshire and Carmarthenshire to Swansea, Merthyr,

Newport and Chepstow where on 16 November he took the train to London.

In the sweeping away of many of his more curious ideas, especially in the field of

Welsh and Celtic philology. It is doubtful, for example, whether anyone would now

maintain, as Borrow did in the first paragraph of his introduction to Wild Wales,

that the words Wales and Vulcan were cognate - Yet, although Borrow's knowledge of

Wales was inadequate and although Wales as a whole did not engage his attention,

his account of his visit captured some of the essence of the country at the exact

time when it was on the verge of massive changes. The origins of these changes were

discernible when Borrow undertook his tour. He did not discern them, but in a sense

he did something more important. He portrayed the mood of the Welsh people at the

very moment when they were poised on the brink of transformation. And he did so with

such aplomb.

In the previous article about the travels of Gerald the Cymro (Giraldus Cambrensis)

around Wales of the twelfth century we do not meet the real people that were being

wooed to accompany the venerable Archbishop Baldwyn. But enough comes through the

pedantic writing of the holy man to enable the reader to form some idea of the developed

society that existed in the rugged country that was and still is Wales. George Borrow

takes pride in his so-called mastery of the Welsh language, but he does not really

portray the talent that exists in the literary field of bardic tradition.

|